Did you know?

Often the First World War is reported and commemorated for its staggering casualties and heavy impact on the world and our nation. However, it can also be very interesting with a lot of surprising and unusual facts. Below is a collection of lesser known, yet fascinating facts to help discover another side of the First World War.

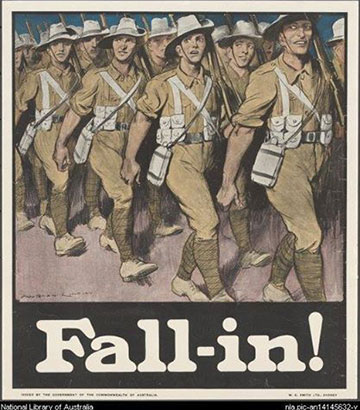

First ashore at Gallipoli

Image: 9th Battalion marching through Queen Street Brisbane 1914.

Source: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Queensland soldiers of the 9th Battalion were first ashore at Gallipoli around 4.30 am 25 April 1915.

The 3rd Australian Field Ambulance (under the command of a Queensland man, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Sutton) were close behind, landing in an area known still to this day as Queensland Point.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial and 9th Battalion Association

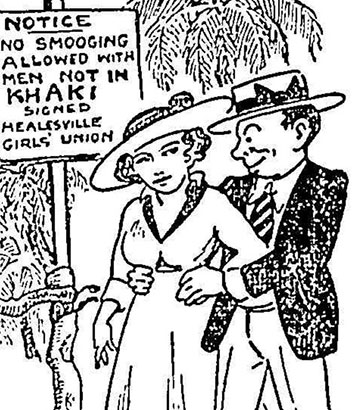

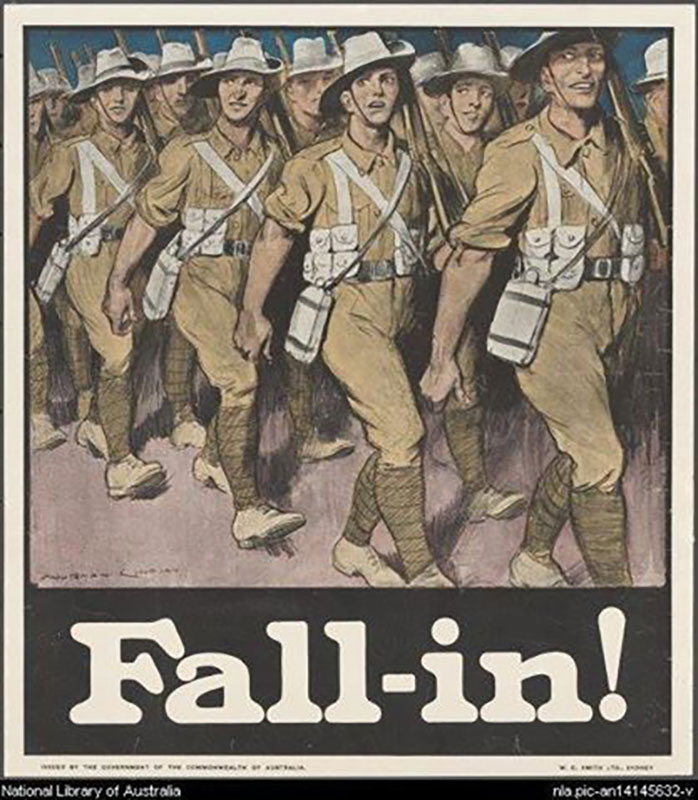

Selective romance

Source: National Library of Australia.

During the First World War, single women in the Victorian town of Healesville banded together to boycott the dating of young men who failed to enlist. "If we’re not good enough to fight for, we’re not good enough to smoodge with" they declared. (Smoodge was slang for kissing and cuddling).

This cartoon appeared in a Melbourne newspaper called Truth on 3 February 1917.

Further reading: Nine.com.au

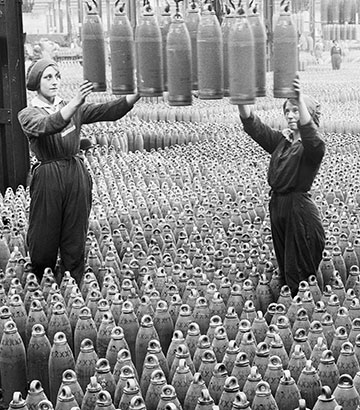

Women in the workforce

Source: Imperial War Museums

Photographer: Horace Nicholls

During the First World War many women helped the war effort by working in explosives factories. Unfortunately the poisons in TNT made many very ill, and around 400 women in the UK died from overexposure to TNT while the war raged.

This picture shows women working with howitzer shells at the Chilwell factory in Nottinghamshire in July 1917. A year later, eight tons of TNT exploded at the plant, killing 134 people, injuring a further 250 and destroying a substantial part of the factory. The blast was heard up to 250 miles away.

Further reading: Australian women in wartime

Women on the frontline

A handful of women served on the frontlines of the First World War. A young English reporter, desperate for a great story, fought on the Somme disguised as a Tommy in 1915. Although only 17, Nadeshda Degtereva disguised herself as a boy and joined the Russian air service, lying that she was aged 19. In 1917 Loretta Walsh became the first American active-duty Navy woman.

Flora Sandes (photographed) enlisted as a volunteer with St John Ambulance and, when separated from her unit, joined a Serbian regiment for safety. She took up the rifle and became the first woman to be commissioned as an officer in the Serbian army and the only British woman to officially enlist as a soldier in the First World War. And in 1917, the Russian Government created 15 women-only battalions who fought against the Germans at the Kerensky Offensive.

Further reading: War History Online

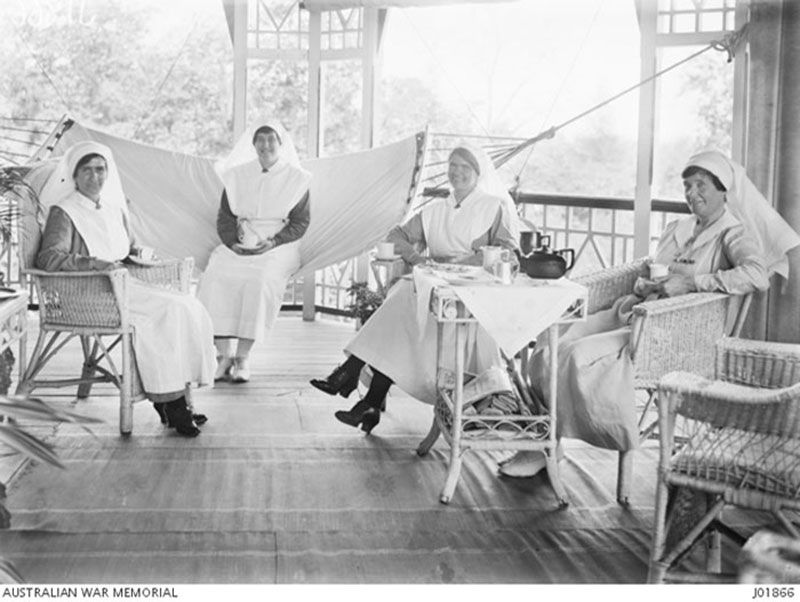

Caring for the soldiers

Source: Australian War Memorial JO1866.

More than 3,000 Australian civilian nurses volunteered for active service during the First World War. Matron Grace Wilson and Dorothy Frances Webb from Brisbane were among 22 Queensland nurses awarded the Royal Red Cross.

One of the first operations of the war involved Queensland nurses, or sisters as they were commonly known, in German New Guinea in September 1914. In the first nursing team to serve overseas were Brisbane nurses Matron Robertson, Sisters McLean, Nelson, Leatherbridge and Gibbon (photographed).

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Greatcoats doubled as bedding

Image: An Australian soldier in the trenches near Bois Grenier 5 June 1916.

Source: Australian War Memorial EZ0052.

Australian First World War troops were issued identical khaki woollen greatcoats (which weighed about 3kg) and often doubled as bedding.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial and SBS

Australian Light Horse feathers

The distinctive plume of emu feathers worn on the left side of the Light Horseman’s slouch hat was first devised by Queensland mounted troops during the First World War.

Called out on "special duty" during the Great Shearers' Strike in 1891, the Gympie Squadron of the Queensland Mounted Infantry broke the monotony of their long patrols by riding down emus, plucking a feather from the bird, and then decorating their hats with the trophy. In recognition of their service, the Queensland Government allowed the whole regiment to officially wear the plume as part of their uniform.

The emu plume was subsequently adopted by the Australian Light Horse and is still worn today, inseparable from its legend.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Deployed without helmets

Helmets were not issued at the beginning of the First World War. The French were the first to introduce them in 1915. Australian troops were issued with a sun helmet (made of cork) worn mostly in Gallipoli, and between 1916 and 1918 wore the British Brodie helmet in the trenches on the Western Front.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial and Express.co.uk

Socks for the troops

Image: War Chest Sock Appeal, Sydney 1917.

Source: State Library of NSW.

Photographer: G A Hills.

Australians at home knitted over 1.3 million pairs of socks for First World War troops, requiring approximately 10 million hours of work.

Knitters had to closely follow the official Grey Sock pattern published at the time – grey or khaki in colour and without seams to prevent rubbing on the soldiers’ feet. Volunteers checked the quality of donated socks (photographed); those which passed often had a small note placed inside.

In Victoria, when demand for knitted socks exceeded supply, bicycle spokes were turned into knitting needles.

Further reading: The Grey Sock pattern and The Conversation

Lifesaving gas masks

Source: Australian troops wearing gas masks. Image coloured by The Diggers View

The use of poisonous gases caught the allied forces off guard in the First World War. To protect themselves, soldiers were instructed to use a urine-soaked cloth over their face. It wasn’t until about 1917 that gas masks with filters were provided to the troops to protect them from about 30 different noxious gases being used.

Further reading: History Learning Site

Finding the fate of a loved one

Source: Australian War Memorial H02334.

The Australian Base Records Office was established in Melbourne in October 1914. It was responsible for all Australian military personnel records – including Queensland – and handling all queries relating to soldiers. Following the landing at Gallipoli they received as many as 1000 letters a day from families desperate to know the fate of their loved ones.

Staying in touch

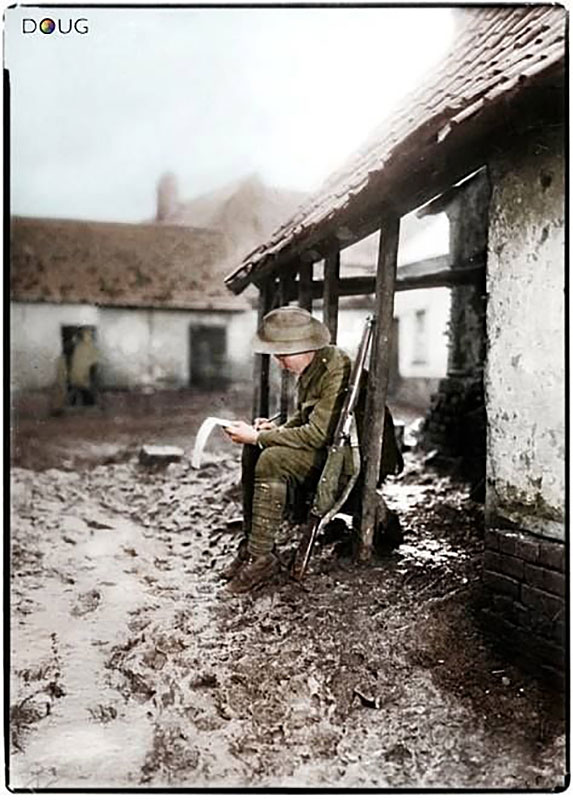

Image: Australian solider on the Western Front 1916.

Source: Australian War Memorial, coloured by WW1 Colourised Photos

It could take up to two months for a letter to reach troops serving overseas during the First World War. Troops had to battle severe weather conditions and the very real challenge of finding paper, pen or pencil and a suitable place in the trenches in order to write a letter home.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Letters become stories

Source: Imperial War Museum

Dr Dolittle was based on a series of letters from a First World War solider writing home to his kids. Not wishing to write about the brutality of war, Hugh Lofting (in photo) instead wrote imaginative letters with illustrations, which later became the foundation of the Dr Dolittle novels, published in 1920.

Further reading: Britannica.com

Three million letters every week

Image: Christmas mail being delivered to frontline.

Source: Library and Archives Canada PA-002263.

More than three million letters from the UK were delivered to the First World War front every week. By the end of the war, two billion letters and 114 million parcels had been sorted by hand and delivered – and that was just the UK post.

The inspiration for Winnie-the-Pooh

Image: Harry Colebourn and Winnie, 1914.

Source: The Canadian Press.

The inspiration for the Winnie-the-Pooh stories can be traced to a black bear called Winnipeg, who was a First World War Canadian Brigade mascot.

In 1914, while en route to England to serve in the First World War, Harry Colebourne purchased a young female black bear cub from a hunter who had killed her mother near White River, Ontario.

He named the bear 'Winnipeg' after his hometown, 'Winnie' for short. As they travelled to Britain with the Brigade, Winnie soon gained recognition as the men’s mascot.

When the Brigade was posted to the battlefields of France, Colebourn took Winnie to the London Zoo and later formally donated her in 1919. Winnie was a very popular attraction. One of her most frequent visitors was Christopher Milne, son of English author A. A Milne. The boy named his teddy bear after Winnie. The relationship between Christoper and his bear inspired A. A Milne's to write the classic children's book Winnie-the-Pooh, published in 1926. The real Winnie went on to live until 1934.

Further reading: Just Pooh.com

Dogs served too

Image: Behind the enemy lines a British solider removes a note from a German messenger dog.

Over 20,000 dogs served with allied forces in the First World War, both as messengers and to help lay telegraph wires. Dogs serving with Australian troops were supplied by the British and tended to be medium sized breeds such as Airedales, collies and German shepherds. Smaller dogs like terriers were often adopted as companions or battalion mascots, and could be put to work hunting rats.

Further reading: Animals in war and Australian War Memorial

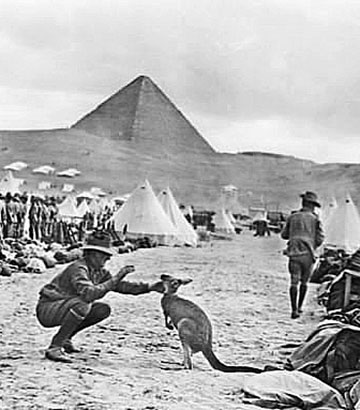

How did a Kangaroo get to Egypt?

Source: Australian War Memorial C02588

In the First World War, some resourceful Australian soldiers smuggled a baby kangaroo into Egypt. The joey became the mascot for the 9th and 10th Infantry Battalions. Smuggling native animals abroad was not uncommon, and many of the animals were donated to local zoos when units were sent to the frontline.

Further reading: Australia Geographic

Horses and their service

Image: Men of the original (1st) Light Horse Regiment at Roseberry Park Camp, near Merriwa, NSW, before departure from Australia.

Source: Australian War Memorial J00450.

Australia sent more than 120,000 horses to the First World War. They performed various roles and were involved in many notable battles. The horses worked under harsh conditions with little food and water – at times carrying loads of almost 130kg.

At the end of the First World War about 13,000 horses remained, but due to quarantine concerns they were unable to be returned home. They were meticulously classified according to age and fitness. Many were re-issued to other Imperial forces, others were sold to French and Belgium locals – only after being assured they wouldn’t be killed for meat. Approximately 3000 were deemed unsuitable for re-issue and were humanely destroyed under veterinary supervision.

Sadly only one horse (Sandy) returned home.

Did you know that horses recruited for the Australian Light Horse had to be a minimum of 14.5 hands high and of a solid colour?

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Impact on the Western Front

Image: Shell cases found from the Western Front during the Iron Harvest.

Photographer: Luke J Spencer

Approximately one tonne of explosives was fired for every square metre of the Western Front in the First World War. Farmers in the area are still finding large volumes of unexploded bombs, barbed wire, shrapnel and bullets which are collected during the annual spring ‘iron harvest’. It is important to remove these items carefully, as buried First World War ordnance has sadly killed 358 civilians and injured a further 535 since 1919. In 2013 alone, 160 tonnes of munitions were unearthed from the area around Ypres.

Further reading: Atlas Obscura and The Times.co.uk

Revealing the enemy’s position

Source: Imperial War Museums Q17779

Papier-mâché dummy heads were used during the First World War to draw out enemy snipers. The decoy heads were mounted on sticks and poked above the trench line, tempting the enemy to fire and reveal their position.

Further reading: Imperial War Museums

Who was the first to use deadly gas?

Image: 45th Battalion at Ypres in 1917. Image coloured by WW1 Colourised Photos.

Photographer: Frank Hurley.

The first recorded gas attack in the First World War was deployed by the French, with Germany adopting the technology not long after. Initially the use of chemical weapons just made the other side cry or sneeze, albeit making it hard to defend themselves. But by 1915, both sides were using deadly gases to aid in breaking the stalemate in the Western Front trenches. In total, more than 91,000 died due to gas warfare.

Further reading: History Learning Site

Male and female tanks

Source: Australian War Memorial E02876.

In the First World War there were female and male tanks. Male tanks had six pounder guns, female tanks only had machine guns. In 1918 it was decided that tanks should carry both which then became the standard model for tank designs, seeing the end of male and female tanks.

Featured in this image is a German A7V Sturmpanzerwagen. Only 20 were ever built. They saw limited service on the Western Front in 1918, and today only one survives – number 506, “Mephisto” (photographed), which now resides in Queensland.

After being bogged and abandoned on the battlefield near the French town of Villers-Bretonneux, Mephisto was recovered on 14 July 1918 by a largely Queensland Battalion, as well as members of the 26th Battalion and the 1st Gun Carrier company, 5th Brigade of Tanks. After it was recovered from the battlefield and studied by the allies, Mephisto was despatched to Australia.

Australia’s, and the world’s, most significant and dramatic war relic, Mephisto spent much of the Anzac Centenary on loan to the Australian War Memorial, where it underwent conservation work. In 2017, the tank returned to Queensland and was displayed at The Workshop Rail Museum, Ipswich. Then in February 2018, Mephisto made the return journey to the Queensland Museum where it will go on permanent display in the new Anzac Legacy Gallery.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial and Queensland Museum

Life in the trenches

Image: British solider asleep in trench.

Source: National Library of Scotland.

It’s hard to know exactly how many kilometres of trenches there were on the Western Front. That said, it’s believed that the allies’ network, if laid end to end, would have stretched approximately 20,000 km – that’s nearly the entire coastline of Australia.

First World War soldiers could spend anywhere from one day up to several weeks at a time in the trenches. This consisted of time in the frontline trenches, support trenches and also time resting. Even while “resting” on the frontline, soldiers had work to do – repairing trenches, moving supplies, cleaning weapons, undergoing inspections or guard duty.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial and Kids Connect

Clever disguise

During the First World War, German troops studied and photographed the last few trees on the Western Front to make replicas, which were actually observation posts. At night, under the cover of artillery fire, the replica trees were installed, allowing troops to watch enemy movements without being seen.

The Australian War Memorial features the only observation post of its kind left in the world. Brought back from Oosttaverne Wood near Messines in Belgium (1917), it features the signatures of Australian soldiers serving at the time including Queenslander Private John Patrick Rochrig.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial.

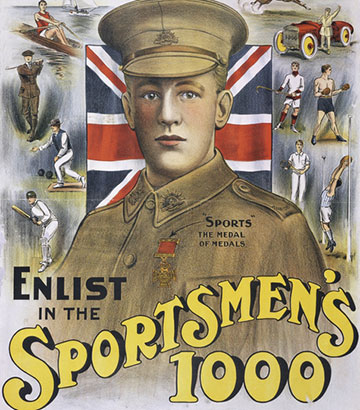

The impact on Australian sports

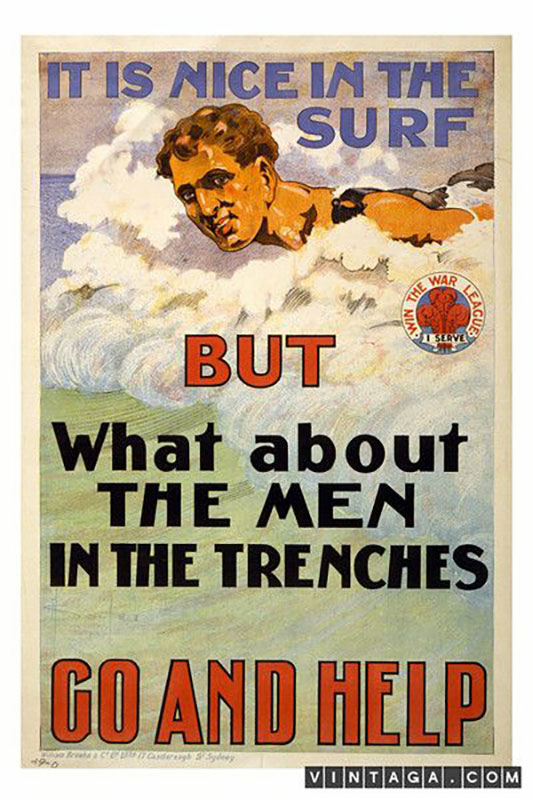

Image: Australian First World War poster.

Source: Australian War Memorial ARTV05616.

Cricket, Rugby and Aussie Rules were popular with First World War troops during rest time. They even had their own version of state of origin with inter-battalion footy games. Sport was a reminder of the joys of life before war. However, sporting codes at home were greatly affected as many players enlisted and recruitment drives targeted athletes for their endurance and physical strength.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial, State Library of Queensland and ABC

The first motorised Ambulances

Source: Disney Enterprises.

The first ever motorised ambulances were used during the First World War. Thousands of men and women volunteered as ambulance drivers including the famous animator Walt Disney at the age of 16, who decorated his vehicle with cartoons (photographed).

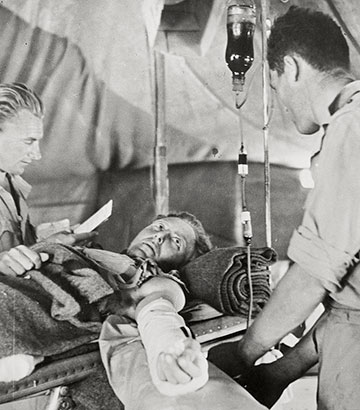

Blood transfusions on the frontline

Image: Solider receiving a blood transfusion during First World War.

Source: Wellcome Images L0024143.

A US Army doctor established the first blood bank on the Western Front in 1917. Blood was kept on ice for up to 28 days then transported to casualty stations for use in life-saving surgery for allied forces, no doubt saving thousands of Australian men. The British Army also began the routine use of blood transfusion in the First World War.

Further reading: BBC

The Spanish flu

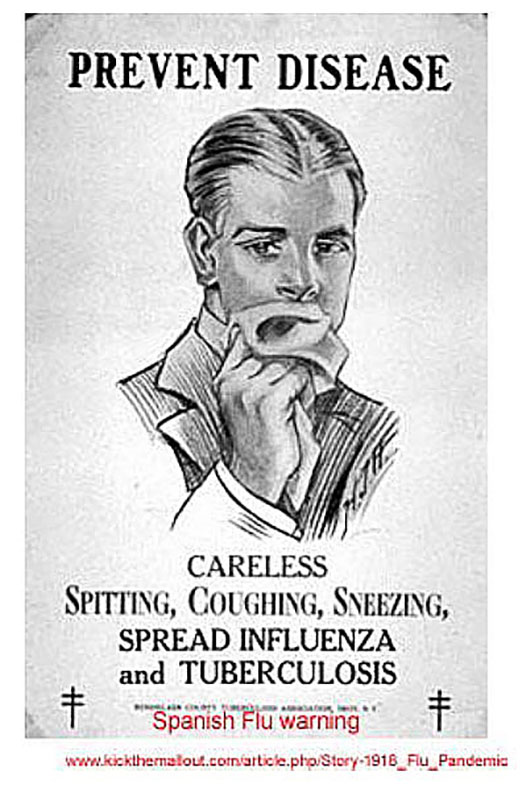

Image: First World War Spanish flu poster.

The deadliest flu outbreak in history occurred at the end of the First World War (1918-19) claiming about 50 million lives worldwide – almost three times the number killed during the war (17 million). At the time, this was almost a third of the world’s population.

Further reading: History.com

The familiar comfort of a cuppa

Image: Australian soldier enjoys a cup of tea at the Australian Comforts Fund stall, Longueval, France, December 1916. The soldier serving is thought to be Private Alexander Gunn.

Source: Australian War Memorial E00034.

Volunteers served over 12 million cups of tea and coffee to the First World War troops. In tents, dugouts and hastily assembled huts at the corner of every Australian battlefield, the Australian Comforts Fund stalls served mugs of tea and coffee to exhausted troops trudging in and out of the frontline.

Further reading: Digger History, and Museums Victoria Collections

Trench menu

Image: Men of the 2nd Australian Division in a frontline trench near Armentieres, cooking a meal.

Photographer: Ernest Brooks.

Source: Imperial War Museums Q 583.

Frontline First World War troops often ate the same rations of tinned corned beef (also known as Bully beef) and hard biscuits for months at a time.

The original Anzac biscuit (also known as the Anzac 'tile'), was part of army rations given to Anzac soldiers. Unlike the popular Anzac biscuits of today, Anzac 'tiles' had a long shelf life, were made mainly from flour and water, and were hard tack, often breaking soldier’s teeth. Soldiers devised ingenious methods to make them easier to eat. A kind of porridge could be made by grating them and adding water. Or biscuits could be soaked in water and, with jam added, baked over a fire into jam tarts. Not at all like what Nanny cooks us today.

Further reading: Anzac Tile AWM, Sydney Morning Herald and Good Food.com.au

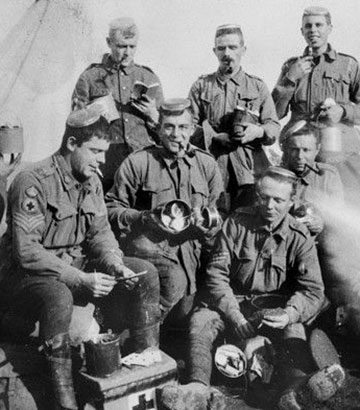

The Christmas billy tin

Image: Members of 4th Australian Field Ambulance displaying their Christmas billies in January 1916. The men are wearing the lids on their heads.

Source: Australian War Memorial P01116024.

One of the most popular care parcels Australian soldiers received for Christmas in 1915 was the humble billy tin. Known as the Christmas billy, they were put together by families back home and contained a plum pudding and items such as tobacco/cigarettes, razor blades, coffee, tinned fruit, knitted socks, writing paper, sauces and cake. New socks were particularly welcomed due to the cold, wet winters. Almost 50,000 billies were issued to soldiers to share, one gift between two.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Queensland towns named after the Western Front

Did you know there’s a town in Queensland called Pozieres? Originally a soldier settlement village, the town took the name Pozieres after the First World War to commemorate the selfless contributions made by the men and women who served in France on the Western Front. Pozieres is located about 215 km west of Brisbane.

Female aviators

Source: The Library of Congress.

Women were flying planes before the First World War. Some taught fighter pilots, while a handful of Russian women and one French women actually flew combat missions.

In the US, Marjorie and Katherine Stinson trained over 100 Canadian cadet pilots at their San Antonio flying school. At the time, Katherine (pictured in 1915) was 24, while Marjorie was 18 years old.

Further reading: Monash.edu.au

The inception of Anzac Day

Image: Anzac Day, Brisbane 1916.

Source: National Archives of Australia J2879, QTH173.

Anzac Day as we know it today, was devised by Queenslanders.

On 10 January 1916, the Mayor of Brisbane called for a public meeting where the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee of Queensland (ADCC) was formed. It’s said that Thomas Augustine Ryan, a Brisbane auctioneer, put forward the suggestion that 25 April (the landing at Gallipoli) be allocated as a day of solemn remembrance. The Committee then tasked Chaplain Canon David John Garland (later referred to as the ‘architect of Anzac Day’) to devise Queensland’s Anzac Day activities. He and others of the committee worked tirelessly to successfully lobby leaders throughout Australia, New Zealand and London to adapt Queensland’s plans and host their own Anzac Day commemorations.

Further reading: Anzac Day Commemoration Committee and Australian War Memorial

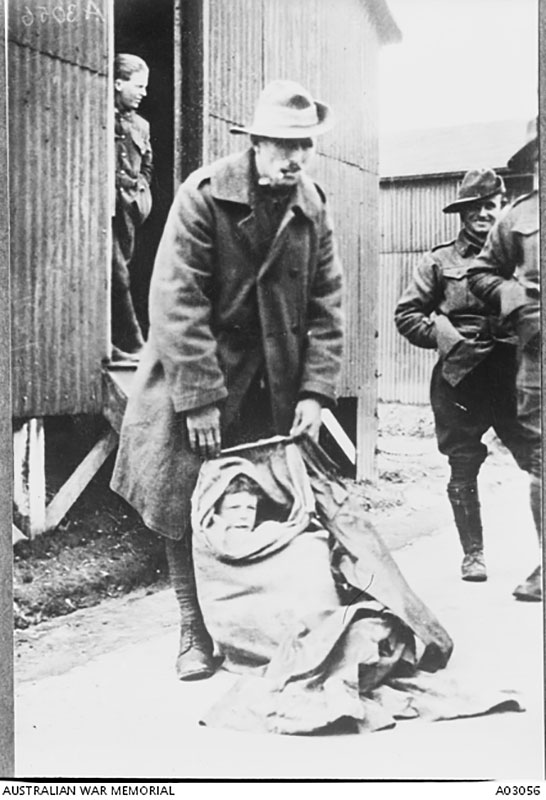

French orphan smuggled back to Queensland

Image: Private Tim Tovell and Henri.

Source: Australian War Memorial A03056.

A French orphan was smuggled back from Europe to Queensland by Australian troops after the First World War.

In December 1918, near an airfield in Cologne, Germany, Henri, a five year old French orphan, wandered into a Christmas dinner attended by the No. 4 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps. Henri was nicknamed 'Digger' by the airmen and quickly became the Squadron's mascot. He developed a strong bond with one solider from Queenslander, Private Tim Tovell.

Henri moved with the squadron in 1919 to France, and later England, where a special tailored AIF uniform was made for him. When the squadron embarked for Australia on 6 May 1919, it was agreed Henri should return to Australia with them. It’s believed that Tovell arranged a specially prepared oat sack to smuggle Henri aboard.

Upon his arrival to Queensland Henri was accepted as a family member at the Tovells’ home in Jandowae. The French Consul agreed that Henri could be adopted by Tim Tovell but would not be naturalised until the age of 21. At the age of 18 Henri left for Melbourne to work for the RAAF. Sadly Henri died in a motor cycle crash in 1928 aged 20.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Queensland's last surviving First World War veteran

Source: John Oxley Library, Edward David Smout, The Queenslander Pictorial 9 September 1916.

Queensland's last surviving First World War veteran was Edward David (Ted) Smout.

In 1915, Edward Smout lied about his year of birth to enlist at the young age of 17. For his exploits during the war, he was awarded France's highest honour, being made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion d'Honneur in 1998. Corporal Smout also received the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to the community.

As a regular participant in Anzac Day parades, Corporal Smout died aged 106 in 2004 and was one of the last six Australian survivors from the First World War.

The Ted Smout Memorial Bridge, named in honour of the First World War veteran, is 2.7km long and links Brisbane and Redcliffe. His biography, Three Centuries Spanned, was published when he was 103.

Further reading: Telegraph.co.uk

The first to serve

Image: First troops leaving Townsville August 1914.

Source: State Library of Queensland 25536.

Australia did not enter the First World War with the landing on Gallipoli.

When war was declared 4 August 1914, the most immediate military threats lay to Australia’s north in German New Guinea and on Thursday Island in the Torres Strait where Germany had wireless (radio) stations on islands in the Pacific region.

In less than 10 days a 1000 strong infantry battalion, 500 naval reservists and ex-seamen, and a 500 strong citizen-battalion from north Queensland had been recruited, equipped and dispatched.

Many of the men were from North and Far North Queensland rifle clubs who bravely left their lives and family behind, stepping into action. Departing from Cairns on 11 August, they joined the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) bound north towards German New Guinea and ultimately travelling onto Rabaul.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial

Queensland's contribution

Source: Australian War Memorial ARTV00141.

416,809 Australian men (including 57,705 from Queensland) enlisted for the First World War, representing about 38% of the male population aged 18-44 at the time. Of these men, more than 60,000 were killed and 156,000 wounded or taken prisoner.

This 1915 recruitment poster was issued by the Win the War League. Depicting a young man enjoying himself in the surf, the text reminds the community that while young, able-bodied men can enjoy their recreational activities, they are forgetting about those serving in the trenches. This poster was clearly designed to appeal to a sense of patriotism and pride to encourage young men to enlist.

| State | Total Enlistments | Percentage of Population | Percentage of males aged 18 to 44 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Australia | 32,231 | 9.9 | 37.5 |

| New South Wales | 164,030 | 8.8 | 39.8 |

| Queensland | 57,705 | 8.5 | 37.7 |

| South Australia | 34,959 | 8.0 | 37.6 |

| Tasmania | 15,485 | 7.9 | 37.8 |

| Victoria | 112,399 | 7.9 | 38.6 |

| Total | 416,809 |

Further reading: RSL NSW

Queensland in the highest ranks

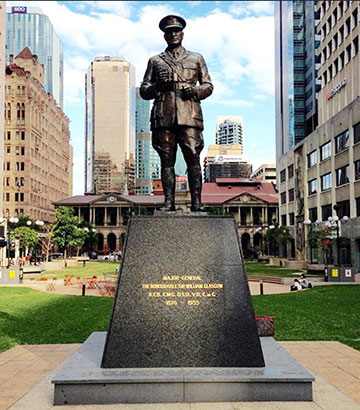

Image: In 1966 a bronze statue of Glasgow by Daphne Mayo was unveiled overlooking Anzac Square, Brisbane.

Born and raised in Queensland, Major General Sir William Glasgow was one of Australia’s highest ranking soldiers in the First World War.

Enlisting in the Queensland Mounted Infantry while still a teenager, he served in the Boer War and by 1912 had achieved the rank of Major. When the First World War broke out, he had only recently relinquished duties at his father’s grocery store in Gympie and bought a cattle station in Queensland, but enlisted immediately with three of his six brothers landing at Gallipoli in May 1915 as a Major in the 2nd Light Horse Brigade.

As acting commandant of Pope's Hill, he led 200 troopers from the Australian Light Horse in an attack on Dead Man's Ridge. He was among the last to retire that day, carrying with him one of his wounded troopers and gaining promotion to Lieutenant Colonel the next day. In France he rose to command the 1st Division leading his men in many important actions including Pozières, Messines, Passchendaele, Mouquet Farm and Dernancourt.

Glasgow once responded to a German demand to surrender with “Tell them to go to hell”. After the war, Sir William had a long political career, became Australia's first High Commissioner to Canada, and led the Brisbane Anzac Day parade for 20 years.

Further reading: Australian Dictionary of Biography

The end and the start are connected

Image: Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s vehicle.

Source: www.eastsussexww1.org.uk

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated on 28 June 1914 as their motorcade drove through the streets of Sarajevo, an event which is widely acknowledged to have sparked the beginning of the First World War. Stranger than fiction, the number plate at the time read: A 111 118, which could also be read as Armistice 11 Nov ’18 (the end of the First World War).

Further reading: History.com

Brave indigenous soldiers

Image: Servicemens’ wedding at Charlotte Street, Brisbane, 1917.

Source: John Oxley Library 113148.

Indigenous Australians were present in almost every Australian campaign of the First World War and some were decorated for outstanding actions. Corporal Albert Knight, 43rd Battalion, and Private William Irwin, 33rd Battalion, were each awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal—second only to the Victoria Cross for men in their ranks.

This photo features two Aboriginal troopers from the 11th Light Horse Regiment at their joint wedding prior to disembarking for the war. The grooms are Private James ‘Jim’ Lingwoodock who married Daisy Roberts, and Private John ‘Jack’ Geary with his bride Alice Bond.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial and State Library of Queensland

Conscription

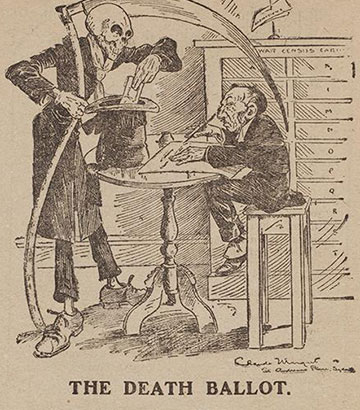

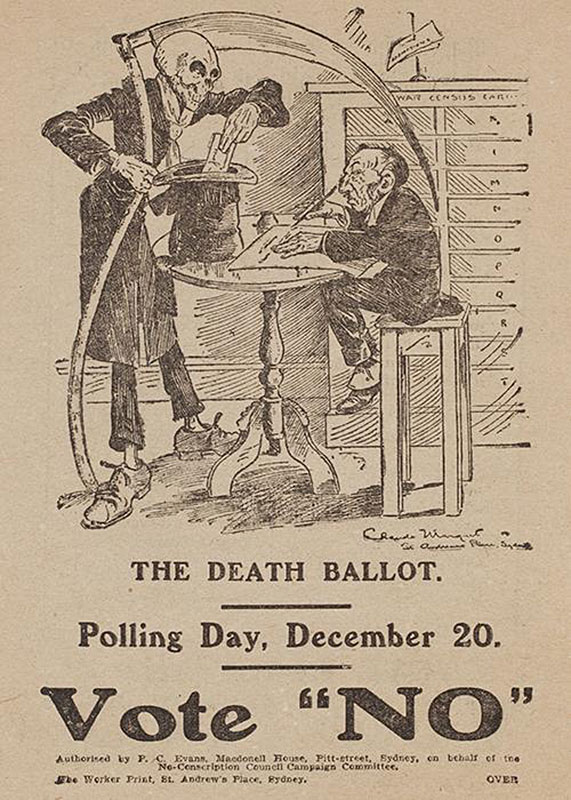

Image: 'The Mothers' anti-conscription campaign, First World War, Australia 1917.

Cartoonist: Claude Marquet.

Source: Museum Victoria collection.

Despite the fact the Australian Imperial Force was desperately short of men, twice during the First World War, a referendum was called for the Australian people to vote on the issue of military conscription (the compulsory enlistment for state service).

Each time the majority of Australia voted “no”. The first referendum in 1916 was defeated with 1,087,557 in favour and 1,160,033 against. The second referendum in 1917 was also defeated with 1,015,159 in favour and 1,181,747 against.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial, National Archives Australia, and News.com.au

The origins of “dog fight”

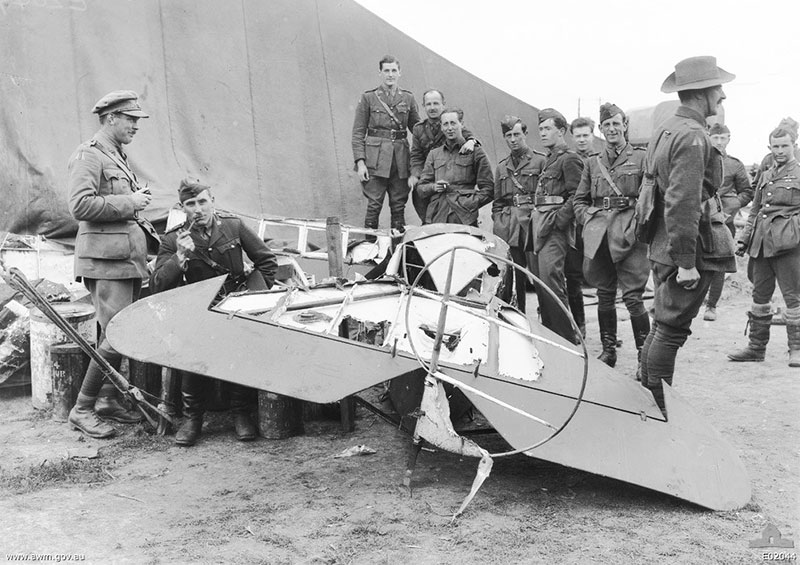

Source: Australian War Museum E02044.

Photographer: Unknown Australian Official Photographer.

The term “dogfight” originated during the First World War. It’s said the term comes from the men in the trenches thinking the aircraft flying above looked like dogs chasing each other. Furthermore, when a plane engine was re-started mid-air, it often sounded like a dog barking. Pilots had to do this from time to time to avoid stalling when turning quickly.

This image, taken 22 April 1918, shows Australian soldiers and airmen with the remains of the Fokker Triplane belonging to the famous Baron von Richthofen—the Red Baron. The German airman was shot down and crashed behind Australian lines during a low level dog fight near the Somme on the Western Front. Fatally struck in the torso by just one bullet—believed to be from Australian army machine gunners in the trenches below—this dramatic event is one of legend. At the time, Von Richthofen’s body was turned over to a nearby Australian fighter squadron who buried him with full military honours. Von Richthofen’s body was disinterred in 1925 and repatriated to Germany for a second funeral.

Further reading: Military History and Australian War Memorial

Families to pay for loved ones tribute

Image: Carving of headstones by hand would take a week.

Source: Commonwealth Graves Commission.

Unlike the Australian Government, the Imperial War Graves Commission (formed in 1917) charged British families three and a half pence (about $6 today) per letter for personal epitaph engravings on First World War head stones. With a limit of 66 letters (including spaces), the IWGC also reserved the right to veto any epitaph it deemed inappropriate, too long, cumbersome, inartistic, or even too sentimental.

Further reading: Air Crew Remembered and WW1 Epitaphs

The ideal solider

Source: National Library of Australia.

The ideal solider in the First World War was aged between 18 and 35 years, 168cm tall, and had a chest measurement of 86cm.

As time passed and it became harder to convince men to enlist, the age regulations were relaxed. The oldest Australian known to have enlisted was aged 70. The youngest known Australian boy to enlist in the First World War was 14 years old. Many of Queensland’s 'boy soldiers' made the ultimate sacrifice. Among them:

- Private Sidney James Joseph Pelin (6072, 15th Battalion) from Mount Morgan, died aged 17.

- Private Ernest Wilson Pinches (296, 5th MG Company) from Brisbane, died aged 17.

- Private Walter James Missingham (5184, 47th Battalion) born in Townsville, died aged 17.

- Private Albert Stanley Scott (949, 15th Battalion) from Gympie, died aged 17 years and 8 months.

Further reading: Australian War Memorial